Ethics of Efficiency: The Human Cost of Variable Labor

Published on Tháng 1 30, 2026 by Admin

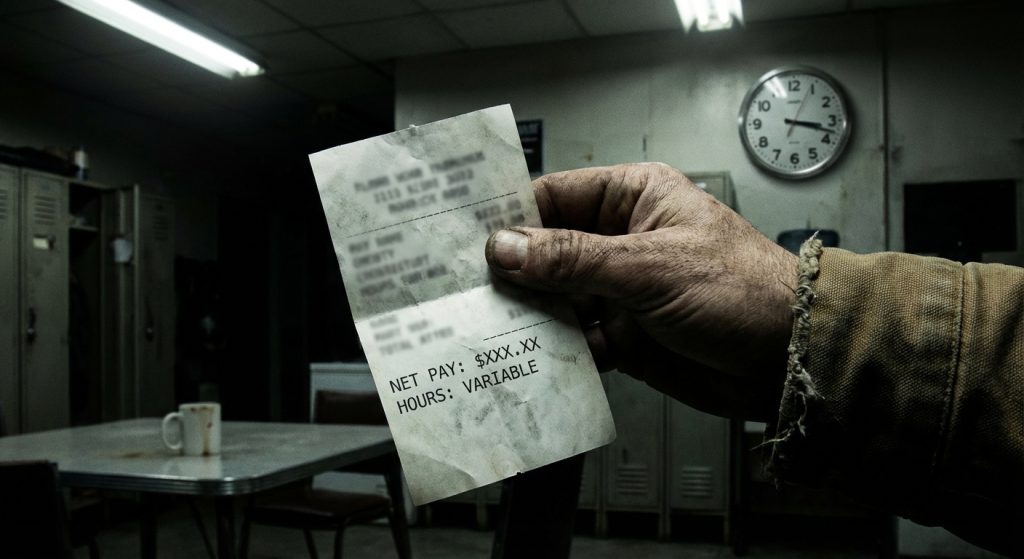

Modern business is obsessed with efficiency. Companies constantly seek ways to deliver more value at a lower cost. As a result, a new model of work has emerged: the variable cost labor environment. This approach promises incredible flexibility and cost savings. However, it also raises profound ethical questions about the human price of this relentless pursuit of efficiency. This article explores the complex ethics of these new labor models.

We will examine the fundamental trade-offs involved. In addition, we will look at the core ethical dilemmas from different philosophical viewpoints. Ultimately, we must ask if we can build a future where efficiency does not come at the expense of human dignity.

The Rise of the Variable Cost Model

The traditional employment model involves fixed costs. For example, employees receive salaries, benefits, and have dedicated office space. These costs remain relatively stable regardless of business volume. In contrast, the variable cost model changes this dynamic entirely.

What is Variable Cost Labor?

Variable cost labor treats human work as a flexible expense. Instead of salaried employees, companies rely on a fluid workforce of freelancers, gig workers, and contractors. Therefore, labor costs rise and fall directly with demand. If a company needs more work done, it hires more task-based workers. If demand falls, it simply stops sending out new tasks.

This model is the engine behind the gig economy. It powers everything from ride-sharing apps and food delivery services to global freelance platforms where you can hire someone for a single project.

Why Companies Embrace It

Businesses adopt this model for several compelling reasons. Firstly, it dramatically reduces fixed overhead. Companies no longer need to pay for idle workers during slow periods. This agility is a significant competitive advantage, especially for new companies. Indeed, many are scaling startup operations with variable labor strategies to grow quickly without massive initial investment.

Moreover, this approach provides access to a global talent pool. A company in New York can hire a programmer in Manila for a fraction of the local cost. This talent arbitrage further drives down expenses and increases efficiency.

Efficiency’s Double-Edged Sword

The shift to variable labor is not just a story of corporate savings. It has a profound and often contradictory impact on the workers themselves. For some, it represents freedom. For others, it creates deep instability.

The Promise of Flexibility and Opportunity

On one hand, this model offers unprecedented flexibility. Workers can often choose when and where they work. This autonomy is highly attractive to students, parents, and anyone seeking to supplement their income. It allows people to become their own boss, escaping the rigid 9-to-5 structure.

Furthermore, it can open doors to new opportunities. A graphic designer in a small town can now work for major international brands. This access can lead to skill development and a more diverse career path than traditional local employment might offer.

The Peril of Precarity and Instability

On the other hand, this flexibility comes at a steep price. The most significant issue is precarity, which is a state of persistent insecurity. Gig workers and freelancers often lack a stable, predictable income. One month can be prosperous, while the next can be a struggle to pay bills.

Because they are classified as independent contractors, these workers typically receive no benefits. This means no health insurance, no paid sick leave, and no retirement contributions from the company. They bear the full risk of illness, economic downturns, and planning for the future.

The Core Ethical Dilemmas

The tension between corporate efficiency and worker precarity creates several fundamental ethical problems. These issues challenge our traditional understanding of work, fairness, and corporate responsibility.

Dehumanization Through Algorithms

In many variable labor platforms, human managers are replaced by algorithms. These systems assign tasks, monitor performance, and even deactivate workers based on data points and customer ratings. This algorithmic management can be brutally efficient. However, it lacks human empathy and context.

A worker might receive a low rating for a late delivery caused by a traffic accident, but the algorithm sees only a failed metric. Consequently, workers can feel like cogs in a machine, managed by an unfeeling system that reduces their humanity to a performance score.

The Erosion of Worker Rights

The classification of workers as “contractors” is a central ethical issue. This legal distinction allows companies to sidestep decades of labor protections. These include minimum wage laws, overtime pay, and the right to form unions. As a result, companies benefit from the control they exert over their workers without shouldering the responsibilities of an employer. This makes many question who really pays the price for the gig economy’s convenience.

This creates a two-tiered labor system. One group has protections and stability, while the other operates in a precarious environment with few safety nets.

Fairness in a Global Marketplace

Variable labor platforms create a single global marketplace for talent. While this offers opportunities, it also creates a race to the bottom. A writer in the United States may be forced to compete with a writer in a country with a much lower cost of living. Consequently, this global competition can suppress wages for everyone.

This raises questions of global justice. Is it ethical for companies to build business models that profit from vast global wealth inequalities? The efficiency gained comes directly from paying workers wages that would be unlivable in the company’s home country.

Philosophical Lenses on the Problem

We can analyze these dilemmas through established ethical frameworks. These philosophical tools help clarify the moral dimensions of the efficiency-first mindset.

A Utilitarian Perspective: The Greatest Good?

Utilitarianism argues that the most ethical action is the one that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people. From this viewpoint, variable labor presents a mixed picture. Consumers benefit from lower prices and greater convenience. Companies and their shareholders benefit from higher profits and agility.

However, the harm done to workers must be weighed in this calculation. The stress, instability, and lack of benefits for millions of workers could create more overall unhappiness than the happiness generated for consumers and shareholders. A true utilitarian analysis would need to quantify this widespread precarity.

A Deontological View: Duties and Rules

Deontology focuses on moral duties and rules, regardless of the consequences. A deontologist might argue that certain actions are inherently right or wrong. For instance, the philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed that we should always treat people as ends in themselves, never merely as a means to an end.

From this perspective, treating labor as a pure variable cost is ethically problematic. It reduces a person to a tool—a “means” to achieve corporate efficiency and profit. It ignores the inherent dignity and value of the worker as a human being who deserves stability and respect. Therefore, the entire model could be seen as fundamentally flawed, no matter how efficient it is.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main ethical issue with the gig economy?

The primary ethical issue is the misclassification of workers as “independent contractors.” This allows companies to avoid providing basic labor protections like minimum wage, health benefits, and paid leave, placing the full burden of risk on the individual worker.

Can efficiency and ethics coexist in business?

Yes, but it requires conscious effort. Ethical efficiency involves finding ways to be productive and cost-effective without compromising worker dignity and well-being. This might mean investing in technology that supports workers or adopting business models that share risks more equitably.

Are all variable labor models inherently unethical?

Not necessarily. True freelance work, where a highly skilled professional has significant autonomy and bargaining power, can be ethical. The problems arise when platforms use the “contractor” label for low-wage workers who have very little control over their work, essentially creating a workforce of pseudo-employees without rights.

What can be done to protect workers in these environments?

Solutions could include new government regulations that create a third category of worker with some protections. In addition, portable benefit systems that are not tied to a single employer could provide a safety net. Finally, greater transparency in algorithmic management would give workers more power and understanding.

Conclusion: Rebalancing the Scales

The pursuit of efficiency in variable cost labor environments has reshaped our economy. It has unlocked innovation and convenience, but it has come with a significant human cost. The current model often shifts all the risk onto the most vulnerable individuals, creating a system that is efficient but ethically unbalanced.

Moving forward, the challenge for academics, policymakers, and business leaders is to rethink this equation. We must find a way to harness the flexibility of modern work without sacrificing the security and dignity of the people who perform it. Ultimately, the goal should be to build an economy that is not only efficient but also just.

“`